Snake Solver CS 175: Project in AI

Project Summary

Approach

General Overview

For this project, we employ Reinforcement Learning (RL) to train an AI agent to play the Snake game effectively. Given the large state-space of the game (numerous possible configurations of the snake and fruit on the grid), we opt for policy-based, model-free RL methods. Specifically, we use two algorithms: Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C) and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), both implemented via the Stable-Baselines3 library. These algorithms directly learn a policy (a mapping from states to actions) without modeling the environment’s dynamics, making them suitable for our scenario.

Our approach involves setting up a Gymnasium environment to simulate the Snake game, defining the observation space, action space, and rewards, and then training the A2C and PPO models to maximize the snake’s score. Below, we detail the environment setup and the training process, including how A2C and PPO work internally.

Setting Up the Snake Game Environment

We use Gymnasium to create a custom RL environment for the Snake game. The environment is defined as follows:

- Observation Space: A 3D NumPy array of integers representing the game arena. Each cell in the grid is assigned a value:

0for empty space,1for the fruit,2for the snake’s body. The array’s dimensions are[height, width, channels], where channels encode the state of each cell.

- Action Space: Discrete with four possible actions:

{0: Up, 1: Down, 2: Right, 3: Left}. - Terminal State: The episode ends if the snake hits the wall (goes outside the arena) or collides with its own body.

- Reward Function:

+1when the snake eats the fruit (increasing its length and score),-1when the snake reaches a terminal state (hits the wall or itself),0otherwise (for each step where no fruit is eaten and the game continues).

The Gymnasium environment includes the following key methods:

step(action): Updates the environment based on the given action. The snake moves in the specified direction (Up, Down, Right, or Left). If the action is invalid (e.g., reversing direction into itself), the snake continues in its current direction. Returns the new observation, reward, and whether the episode has ended.reset(): Resets the environment to an initial state. The score is set to zero, the snake starts with a length of 1, and its position and the fruit’s position are randomly initialized within the arena.render(): Generates an RGB image of the current arena for visualization.close(): Terminates the environment.

This setup provides a clean interface for the RL algorithms to interact with the game.

Training Process

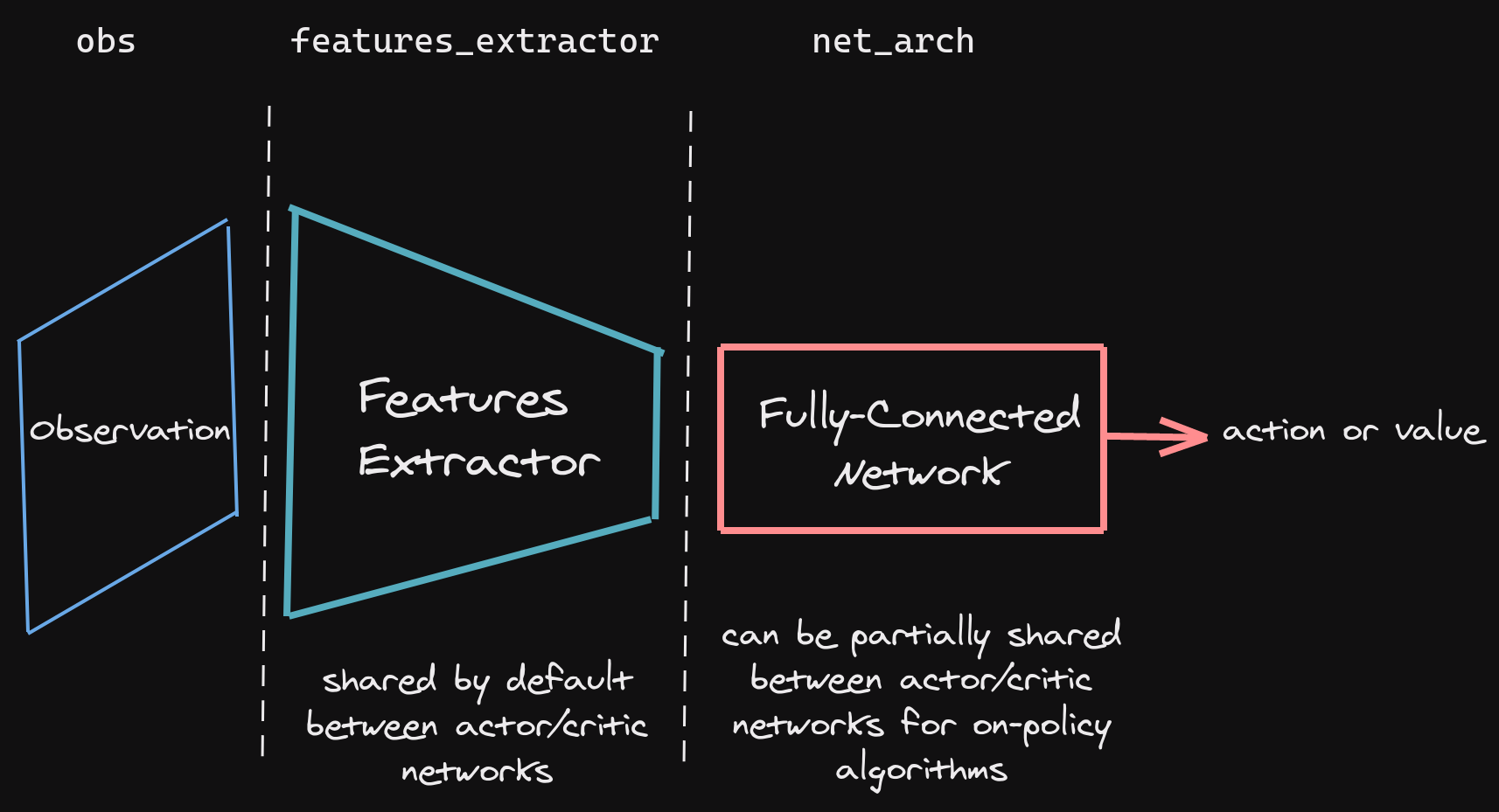

We train two separate models using A2C and PPO from Stable-Baselines3 to compare their performance. Both algorithms process the observation space (the 3D grid) as an image input, using a convolutional neural network (CNN) as a feature extractor to convert the raw grid into a feature vector representing the current state s. This vector is then fed into a policy network to select an action a. The policy network architecture follows the default CNN setup in Stable-Baselines3, as shown below:

Below, we explain how A2C and PPO work and how we apply them to the Snake game.

Training with A2C

A2C is an actor-critic method that combines policy-based and value-based RL. It uses two networks:

- Actor: Learns the policy

π(a|s; θ)—the probability distribution over actions given a state. It selects actions to maximize expected rewards. - Critic: Estimates the value function

V(s; w), which predicts the expected cumulative reward from a given state.

The algorithm updates the actor using the advantage function, defined as: [ A(s, a) = Q(s, a) - V(s) ] where ( Q(s, a) ) is the action-value function (approximated via the reward received and bootstrapped future rewards), and ( V(s) ) is the state-value function from the critic. The advantage measures how much better an action is compared to the average action in that state.

The actor’s policy is updated by maximizing the objective:

[ J(θ) = E[log π(a|s; θ) * A(s, a)] ]

using gradient ascent. Meanwhile, the critic minimizes the loss:

[ L(w) = E[(r + γ * V(s’) - V(s))^2] ]

where r is the reward, γ is the discount factor (set to 0.99 by default), and s' is the next state.

For the Snake game, A2C takes the 3D observation grid, extracts features with the CNN, and outputs action probabilities (e.g., 25% Up, 25% Down, etc.). We train for 10 million timesteps, using Stable-Baselines3’s default hyperparameters: learning rate = 0.0007, n_steps = 5 (steps per update), and and our gamma = 0.99. These values are sourced from the library’s documentation, and we did not tune them further due to computational constraints.

Training with PPO

PPO is a more stable policy gradient method that improves on A2C by constraining policy updates to avoid large, destabilizing changes. Like A2C, it uses an actor-critic framework but introduces a clipped objective function to limit how much the policy can change in each update.

The PPO objective is: [ J(θ) = E[min(r(θ) * A(s, a), clip(r(θ), 1-ε, 1+ε) * A(s, a))] ] where:

-

( r(θ) = π(a s; θ) / π_old(a s; θ_old) ) is the probability ratio between the new and old policies, - ( ε ) is the clipping parameter (default = 0.2),

- ( A(s, a) ) is the advantage, calculated similarly to A2C.

The clipping ensures that the policy doesn’t deviate too far from the previous version, improving training stability. The critic’s loss is the same as in A2C.

For the Snake game, PPO processes the observation grid similarly to A2C, using the same CNN feature extractor. We train for 1 million timesteps with default hyperparameters from Stable-Baselines3: n_steps = 2048, clip_range = 0.2, and our gamma = 0.99 and learning rate = 0.00025. These defaults are well-documented and widely used, so we kept them unchanged.

Hyperparameters and Reproducibility

Both models use the default CNN architecture from Stable-Baselines3 (two convolutional layers followed by a fully connected layer). We train each model for 1 million timesteps, which corresponds to roughly 1 million interactions with the environment (though episodes terminate earlier upon failure). The training data is generated on-the-fly by the Gymnasium environment, so no external dataset is required. For reproducibility, we set a random seed of 42 in both the environment and the algorithms.

Evaluation

We plan to evaluate performance by comparing the average score (total fruit eaten per episode) across 100 test episodes for each model after training. This will determine whether A2C or PPO performs better for the Snake game.

A2C model

- Training evaluation: As shown in fig 02, we observed a mean fluctuation of around 1. Interestingly, we noticed a significant jump in mean score between 3 mil and 4 mil steps. At the end of training, we observed a mean score of 4.18.

- Final evaluation: During final evaluation, we observed a mean reward of approximately 7.

PPO model

- Training evaluation: As shown in Fig 02, we observed a mean fluctuation of around .3. Noticably, there is a jumped in mean score at the beginning. At the end of training, we observed a mean score of 4.7.

- Final evaluation: During final evaluation, we observed a mean reward of approximately 4.8

Observation

- Looking at Figure 2, A2C model performs better than PPO model throughout the training process, as well as final evaluation.

- A problem with A2C model is that at first, it wastes lots of the time for little returns. Figure 5 show the mean episode length for A2C model is much higher and fluctuating than PPO model in the beginning. Yet during those same timesteps, PPO model gets better mean rewards.

Remaining Goals and Challenges

As for our evaluation goal, we have achieved the sanity goal, which was reaching a mean score approximating the length of one side of the arena. However, we are still far from meeting the baseline goal of achieving a mean score equal to half the arena’s size. In retrospect, we may have overestimated our capability and set our baseline goal too ambitious.

Another challenge we’re facing is the length the learning process of both models. They take too long and yet they yield unsatisfying result. We intend to optimize the learning process, taking notes from the AtariWrapper and how it improves the process. Nevertheless, we would like to strive for the baseline goal regardless.

Even if we do not meet the baseline goal, we will still carry out our goal 1, which is spawning obstacles within the arena as well as extra timed fruits that disappear after certain amount of time. In that case, we would like to see how the changes would affect the learning process of both algorithms.

Resources Used:

- Snake Game by PavanAnanthSharma

- Gymnasium for RL environment and documentation.

- Stable-Baseline3 for A2C and PPO implementation, and documentation.

- Series on RL Basics by Luke Ditria

- Blog on PPO Implementation details